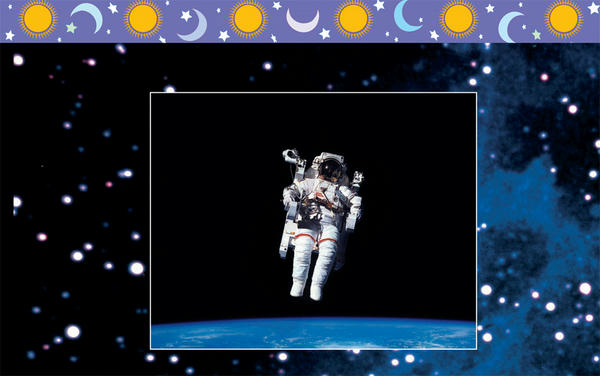

n a very real sense, we are like the spaceman in the photo above, totally dependent on our body, mind, emotions and personal identity to persist in life, just as he depends on his space suit and its supply of oxygen to enable him to exist in space. Take away our body, remove our emotions, erase our identity and what is left? Do we cease to exist? What are we really? Rishis assure us that we are immortal souls on a journey of spiritual evolution. We will take on many bodies, many lives, many different identities through the repetitive cycle of birth, death and rebirth. Each advent into a new birth is like an astronaut’s voyage into the great unknown. The soul’s underlying joy throughout this adventure is to commune with and realize God, learning of its true nature in the great classroom of experience, known as the world, or maya. The three realities of existence, God, soul and world, constitute the fundamentals of Hindu theology, known as tattva-trayi in Sanskrit, describing a view in which Divinity, self and cosmos are a profound, integrated unity. Each and every soul is on the same journey, spanning many lifetimes. The path has been made clear by those who have gone before. The answers to life’s ultimate questions have been given time and time again, but still must be asked and answered by each soul in its own time: “Who am I?” “Where did I come from?” “Where am I going?”

n a very real sense, we are like the spaceman in the photo above, totally dependent on our body, mind, emotions and personal identity to persist in life, just as he depends on his space suit and its supply of oxygen to enable him to exist in space. Take away our body, remove our emotions, erase our identity and what is left? Do we cease to exist? What are we really? Rishis assure us that we are immortal souls on a journey of spiritual evolution. We will take on many bodies, many lives, many different identities through the repetitive cycle of birth, death and rebirth. Each advent into a new birth is like an astronaut’s voyage into the great unknown. The soul’s underlying joy throughout this adventure is to commune with and realize God, learning of its true nature in the great classroom of experience, known as the world, or maya. The three realities of existence, God, soul and world, constitute the fundamentals of Hindu theology, known as tattva-trayi in Sanskrit, describing a view in which Divinity, self and cosmos are a profound, integrated unity. Each and every soul is on the same journey, spanning many lifetimes. The path has been made clear by those who have gone before. The answers to life’s ultimate questions have been given time and time again, but still must be asked and answered by each soul in its own time: “Who am I?” “Where did I come from?” “Where am I going?”

Subtlest of the subtle, greatest of the great, the atman is hidden in the cave of the heart of all beings. He who, free from all urges, beholds Him overcomes sorrow, seeing by grace of the Creator, the Lord and His glory.

Krishna Yajur Veda, Shvetashvatara Upanishad 3.20

ever have there been so many people living on the planet wondering, “What is the real goal, the final purpose, of life?” However, man is blinded by his ignorance and his concern with the externalities of the world. He is caught, enthralled, bound by karma. The ultimate realizations available are beyond his understanding and remain to him obscure, even intellectually. Man’s ultimate quest, the final evolutionary frontier, is within man himself. It is the Truth spoken by Vedic rishis as the Self within man, attainable through devotion, purification and control of the mind. On the following pages, we explore the nature of the soul, God and the world. Offered here is a broad perspective that Hindus of most lineages would find agreement with, though in such matters there naturally arise myriad differences of perspective. To highlight the most important of these we offer a comparison of Hinduism’s four major denominations. Next we explore the views of these four denominations on liberation from the cycle of birth, death and rebirth. Finally, we present a chart of Hindu cosmology that seeks to connect the microcosm and the macrocosm and is a lifetime meditation in itself.

ever have there been so many people living on the planet wondering, “What is the real goal, the final purpose, of life?” However, man is blinded by his ignorance and his concern with the externalities of the world. He is caught, enthralled, bound by karma. The ultimate realizations available are beyond his understanding and remain to him obscure, even intellectually. Man’s ultimate quest, the final evolutionary frontier, is within man himself. It is the Truth spoken by Vedic rishis as the Self within man, attainable through devotion, purification and control of the mind. On the following pages, we explore the nature of the soul, God and the world. Offered here is a broad perspective that Hindus of most lineages would find agreement with, though in such matters there naturally arise myriad differences of perspective. To highlight the most important of these we offer a comparison of Hinduism’s four major denominations. Next we explore the views of these four denominations on liberation from the cycle of birth, death and rebirth. Finally, we present a chart of Hindu cosmology that seeks to connect the microcosm and the macrocosm and is a lifetime meditation in itself.

Who Am I? Where Did I Come From?

Seated by a lotus pond, symbol of his quieted mind, a seeker performs japa and contemplates his destiny, which blooms as naturally as the flower he holds. Behind are depicted the past lives that brought him to his maturity.

ishis proclaim that we are not our body, mind or emotions. We are divine souls on a wondrous journey. We came from God, live in God and are evolving into oneness with God. We are, in truth, the Truth we seek. ¶We are immortal souls living and growing in the great school of earthly experience in which we have lived many lives. Vedic rishis have given us courage by uttering the simple truth, “God is the Life of our life.” A great sage carried it further by saying there is one thing God cannot do: God cannot separate Himself from us. This is because God is our life. God is the life in the birds. God is the life in the fish. God is the life in the animals. Becoming aware of this Life energy in all that lives is becoming aware of God’s loving presence within us. We are the undying consciousness and energy flowing through all things. Deep inside we are perfect this very moment, and we have only to discover and live up to this perfection to be whole. Our energy and God’s energy are the same, ever coming out of the void. We are all beautiful children of God. Each day we should try to see the life energy in trees, birds, animals and people. When we do, we are seeing God in action. The Vedas affirm, “He who knows God as the Life of life, the Eye of the eye, the Ear of the ear, the Mind of the mind—he indeed comprehends fully the Cause of all causes.”

ishis proclaim that we are not our body, mind or emotions. We are divine souls on a wondrous journey. We came from God, live in God and are evolving into oneness with God. We are, in truth, the Truth we seek. ¶We are immortal souls living and growing in the great school of earthly experience in which we have lived many lives. Vedic rishis have given us courage by uttering the simple truth, “God is the Life of our life.” A great sage carried it further by saying there is one thing God cannot do: God cannot separate Himself from us. This is because God is our life. God is the life in the birds. God is the life in the fish. God is the life in the animals. Becoming aware of this Life energy in all that lives is becoming aware of God’s loving presence within us. We are the undying consciousness and energy flowing through all things. Deep inside we are perfect this very moment, and we have only to discover and live up to this perfection to be whole. Our energy and God’s energy are the same, ever coming out of the void. We are all beautiful children of God. Each day we should try to see the life energy in trees, birds, animals and people. When we do, we are seeing God in action. The Vedas affirm, “He who knows God as the Life of life, the Eye of the eye, the Ear of the ear, the Mind of the mind—he indeed comprehends fully the Cause of all causes.”

Where Am I Going? What Is My Path?

An aspirant climbs the highest peak of all, the summit of consciousness. Though the higher reaches of this path are arduous, solitary, even severe, he remains undaunted, impervious to distraction, his eyes fixed firmly on the goal—Self Realization.

e are all growing toward God, and experience is the path. Through experience we mature out of fear into fearlessness, out of anger into love, out of conflict into peace, out of darkness into light and union in God. ¶We have taken birth in a physical body to grow and evolve into our divine potential. We are inwardly already one with God. Our religion contains the knowledge of how to realize this oneness and not create unwanted experiences along the way. The peerless path is following the way of our spiritual forefathers, discovering the mystical meaning of the scriptures. The peerless path is commitment, study, discipline, practice and the maturing of yoga into wisdom. In the beginning stages, we suffer until we learn. Learning leads us to service; and selfless service is the beginning of spiritual striving. Service leads us to understanding. Understanding leads us to meditate deeply and without distractions. Finally, meditation leads us to surrender in God. This is the straight and certain path, the San Marga, leading to Self Realization—the inmost purpose of life—and subsequently to moksha, freedom from rebirth. The Vedas wisely affirm, “By austerity, goodness is obtained. From goodness, understanding is reached. From understanding, the Self is obtained, and he who obtains the Self is freed from the cycle of birth and death.”

e are all growing toward God, and experience is the path. Through experience we mature out of fear into fearlessness, out of anger into love, out of conflict into peace, out of darkness into light and union in God. ¶We have taken birth in a physical body to grow and evolve into our divine potential. We are inwardly already one with God. Our religion contains the knowledge of how to realize this oneness and not create unwanted experiences along the way. The peerless path is following the way of our spiritual forefathers, discovering the mystical meaning of the scriptures. The peerless path is commitment, study, discipline, practice and the maturing of yoga into wisdom. In the beginning stages, we suffer until we learn. Learning leads us to service; and selfless service is the beginning of spiritual striving. Service leads us to understanding. Understanding leads us to meditate deeply and without distractions. Finally, meditation leads us to surrender in God. This is the straight and certain path, the San Marga, leading to Self Realization—the inmost purpose of life—and subsequently to moksha, freedom from rebirth. The Vedas wisely affirm, “By austerity, goodness is obtained. From goodness, understanding is reached. From understanding, the Self is obtained, and he who obtains the Self is freed from the cycle of birth and death.”

What Is the Nature of God?

The face of Lord Siva, worshiped as the Supreme God by millions of Hindus around the world.

od is all and in all, One without a second, the Supreme Being and only Absolute Reality. God, the great Lord hailed in the Upanishads and adored by all denominations of Hinduism, is a one being, worshiped in many forms and understood in three perfections, with each denomination having its unique perspectives: Absolute Reality, Pure Consciousness and Primal Soul. As Absolute Reality, God is unmanifest, unchanging and transcendent, the Self God, timeless, formless and spaceless. As Pure Consciousness, God is the manifest primal substance, pure love and light flowing through all form, existing everywhere in time and space as infinite intelligence and power. As Primal Soul, God is our personal Lord, source of all three worlds. Extolling God’s first Perfection, the Vedas explain, “Self-resplendent, formless, unoriginated and pure, that all-pervading being is both within and without. He transcends even the transcendent, unmanifest, causal state of the universe” (Manduka Upanishad 2.1.2). Describing the second Perfection, the Vedas reveal, “He is God, hidden in all beings, their inmost soul who is in all. He watches the works of creation, lives in all things, watches all things. He is pure consciousness, beyond the three conditions of nature” (Shvetashvatara Upanishad 6.11). Praising the third Perfection, the Vedas recount, “He is the one God, the Creator. He enters into all wombs. The One Absolute, impersonal Existence, together with His inscrutable maya, appears as the Divine Lord, endowed with manifold glories. With His Divine Power He holds dominion over all the worlds” (Shvetashvatara Upanishad 3.1). In summary, we know God in His three perfections, two of form and one formless. We worship His manifest form as Pure Love and Consciousness. We worship Him as our Personal Lord, the Primal Soul who tenderly loves and cares for His devotees—a being whose resplendent body may be seen in mystic vision. And we worship and ultimately realize Him as the formless Absolute, which is beyond qualities and description.

od is all and in all, One without a second, the Supreme Being and only Absolute Reality. God, the great Lord hailed in the Upanishads and adored by all denominations of Hinduism, is a one being, worshiped in many forms and understood in three perfections, with each denomination having its unique perspectives: Absolute Reality, Pure Consciousness and Primal Soul. As Absolute Reality, God is unmanifest, unchanging and transcendent, the Self God, timeless, formless and spaceless. As Pure Consciousness, God is the manifest primal substance, pure love and light flowing through all form, existing everywhere in time and space as infinite intelligence and power. As Primal Soul, God is our personal Lord, source of all three worlds. Extolling God’s first Perfection, the Vedas explain, “Self-resplendent, formless, unoriginated and pure, that all-pervading being is both within and without. He transcends even the transcendent, unmanifest, causal state of the universe” (Manduka Upanishad 2.1.2). Describing the second Perfection, the Vedas reveal, “He is God, hidden in all beings, their inmost soul who is in all. He watches the works of creation, lives in all things, watches all things. He is pure consciousness, beyond the three conditions of nature” (Shvetashvatara Upanishad 6.11). Praising the third Perfection, the Vedas recount, “He is the one God, the Creator. He enters into all wombs. The One Absolute, impersonal Existence, together with His inscrutable maya, appears as the Divine Lord, endowed with manifold glories. With His Divine Power He holds dominion over all the worlds” (Shvetashvatara Upanishad 3.1). In summary, we know God in His three perfections, two of form and one formless. We worship His manifest form as Pure Love and Consciousness. We worship Him as our Personal Lord, the Primal Soul who tenderly loves and cares for His devotees—a being whose resplendent body may be seen in mystic vision. And we worship and ultimately realize Him as the formless Absolute, which is beyond qualities and description.

How Do We Worship the Supreme Being?

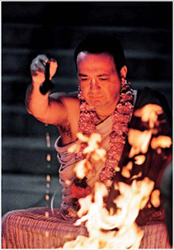

A priest offers ghee into the sacred fire during a homa ritual prescribed in the Vedas that has been performed for thousands of years.

s a family of faiths, Hinduism upholds a wide array of perspectives on the Divine, yet all worship the one Supreme Being, adoring that Divinity as our Father-Mother God who protects, nurtures and guides us. We beseech God’s grace in our lives while also knowing that He/She is the essence of our soul, the life of our life, closer to us than our breath, nearer than hands and feet. We commune with the Divine through silent prayer, meditation, exaltation through singing and chanting, traditional music and dance. We invoke blessings and grace through puja—ritual offering of lights, water and flowers to a sacred image of the Lord—and through homa, or fire ceremony. At least once a year we make a pilgrimage to a distant temple or holy site, devoting heart and mind fully to God. Annual festivals are joyous observances. ¶The four major denominations worship God in their own way. To the Saivite, God is Siva. To the Shakta, Devi, the Goddess, is the Supreme One. The Vaishnava Hindu adores God as Vishnu and His incarnations, and the Smarta worships his chosen Deity as the Supreme. Each denomination also venerates its own pantheon of Divinities, Mahadevas, or “great angels,” who were created by the Supreme Lord and who serve and adore Him. The elephant-faced Lord Ganesha, worshiped by Hindus of all denominations, is the most popular Mahadeva. Other Deities include Gods and Goddesses of strength, yoga, learning, art, music, wealth and culture.

s a family of faiths, Hinduism upholds a wide array of perspectives on the Divine, yet all worship the one Supreme Being, adoring that Divinity as our Father-Mother God who protects, nurtures and guides us. We beseech God’s grace in our lives while also knowing that He/She is the essence of our soul, the life of our life, closer to us than our breath, nearer than hands and feet. We commune with the Divine through silent prayer, meditation, exaltation through singing and chanting, traditional music and dance. We invoke blessings and grace through puja—ritual offering of lights, water and flowers to a sacred image of the Lord—and through homa, or fire ceremony. At least once a year we make a pilgrimage to a distant temple or holy site, devoting heart and mind fully to God. Annual festivals are joyous observances. ¶The four major denominations worship God in their own way. To the Saivite, God is Siva. To the Shakta, Devi, the Goddess, is the Supreme One. The Vaishnava Hindu adores God as Vishnu and His incarnations, and the Smarta worships his chosen Deity as the Supreme. Each denomination also venerates its own pantheon of Divinities, Mahadevas, or “great angels,” who were created by the Supreme Lord and who serve and adore Him. The elephant-faced Lord Ganesha, worshiped by Hindus of all denominations, is the most popular Mahadeva. Other Deities include Gods and Goddesses of strength, yoga, learning, art, music, wealth and culture.

Is the World Also Divine?

An ancient stone carving of Lord Ganesha in Tirupati, is worshiped each day by hundreds of devotees for help and guidance.

es, the world is divine. God created the world and all things in it. He creates and sustains from moment to moment every atom of the seen physical and unseen spiritual universe. Everything is within Him. He is within everything. God created us. He created the Earth and all things upon it, animate and inanimate. He created time and gravity, the vast spaces and the uncounted stars. He created night and day, joy and sorrow, love and hate, birth and death. He created the gross and the subtle, this world and the other worlds. There are three worlds of existence: the physical, subtle and causal, termed Bhuloka, Antarloka and Brahmaloka. The Creator of all, God Himself, is uncreated. He wills into manifestation all souls and all form, issuing them from Himself like light from a fire or waves from an ocean. Rishis describe this perpetual process as the unfoldment of thirty-six tattvas, stages of manifestation, from the Siva tattva—Parashakti and nada—to the five elements. Creation is not the making of a separate thing, but an emanation of Himself. God creates, constantly sustains the form of His creations and absorbs them back into Himself. The Vedas elucidate, “As a spider spins and withdraws its web, as herbs grow on the earth, as hair grows on the head and body of a person, so also from the Imperishable arises this universe.”

es, the world is divine. God created the world and all things in it. He creates and sustains from moment to moment every atom of the seen physical and unseen spiritual universe. Everything is within Him. He is within everything. God created us. He created the Earth and all things upon it, animate and inanimate. He created time and gravity, the vast spaces and the uncounted stars. He created night and day, joy and sorrow, love and hate, birth and death. He created the gross and the subtle, this world and the other worlds. There are three worlds of existence: the physical, subtle and causal, termed Bhuloka, Antarloka and Brahmaloka. The Creator of all, God Himself, is uncreated. He wills into manifestation all souls and all form, issuing them from Himself like light from a fire or waves from an ocean. Rishis describe this perpetual process as the unfoldment of thirty-six tattvas, stages of manifestation, from the Siva tattva—Parashakti and nada—to the five elements. Creation is not the making of a separate thing, but an emanation of Himself. God creates, constantly sustains the form of His creations and absorbs them back into Himself. The Vedas elucidate, “As a spider spins and withdraws its web, as herbs grow on the earth, as hair grows on the head and body of a person, so also from the Imperishable arises this universe.”

Should Worldly Involvement Be Avoided?

The sleek towers of Singapore’s famous Raffles Place exemplify our contemporary high-tech world.

he world is the bountiful creation of a benevolent God, who means for us to live positively in it, facing karma and fulfilling dharma. We must not despise or fear the world. Life is meant to be lived joyously. ¶The world is the place where our destiny is shaped, our desires fulfilled and our soul matured. In the world, we grow from ignorance into wisdom, from darkness into light and from a consciousness of death to immortality. The whole world is an ashrama in which all are doing sannyasin. We must love the world, which is God’s creation. Those who despise, hate and fear the world do not understand the intrinsic goodness of all. The world is a glorious place, not to be feared. It is a gracious gift from God Himself, a playground for His children in which to interrelate young souls with the old—the young experiencing their karma while the old hold firmly to their dharma. The young grow; the old know. Not fearing the world does not give us permission to become immersed in worldliness. To the contrary, it means remaining affectionately detached, like a drop of water on a lotus leaf, being in the world but not of it, walking in the rain without getting wet. The Vedas warn, “Behold the universe in the glory of God: and all that lives and moves on Earth. Leaving the transient, find joy in the Eternal. Set not your heart on another’s possession.”

he world is the bountiful creation of a benevolent God, who means for us to live positively in it, facing karma and fulfilling dharma. We must not despise or fear the world. Life is meant to be lived joyously. ¶The world is the place where our destiny is shaped, our desires fulfilled and our soul matured. In the world, we grow from ignorance into wisdom, from darkness into light and from a consciousness of death to immortality. The whole world is an ashrama in which all are doing sannyasin. We must love the world, which is God’s creation. Those who despise, hate and fear the world do not understand the intrinsic goodness of all. The world is a glorious place, not to be feared. It is a gracious gift from God Himself, a playground for His children in which to interrelate young souls with the old—the young experiencing their karma while the old hold firmly to their dharma. The young grow; the old know. Not fearing the world does not give us permission to become immersed in worldliness. To the contrary, it means remaining affectionately detached, like a drop of water on a lotus leaf, being in the world but not of it, walking in the rain without getting wet. The Vedas warn, “Behold the universe in the glory of God: and all that lives and moves on Earth. Leaving the transient, find joy in the Eternal. Set not your heart on another’s possession.”

Different Views of God, Soul & World… from Hinduism’s Four Denominations

As explained in Chapter Two, there is a wide spectrum of religious belief within Hinduism’s four major sects or denominations: Saivism, Shaktism, Vaishnavism and Smartism. While they share far more similarities than differences, they naturally hold unique perspectives on God, soul and the world. In Saivism, the personal God and primary temple Deity is Siva. He is pure love and compassion, both immanent and transcendent, pleased by devotees’ purity and striving. Philosophically, God Siva is one with the soul, a mystic truth that is ultimately realized through His grace. ¶In Saktism the personal Goddess is Shri Devi or Shakti, the Divine Mother, worshiped as Kali, Durga, Rajarajeshvari and Her other aspects. Both compassionate and terrifying, pleasing and wrathful, She is assuaged by sacrifice and submission. Emphasis is on bhakti and tantra to achieve advaitic union. ¶For Vaishnavism the personal God and temple Deity is Vishnu, or Venkateshwara, a loving and beautiful Lord pleased by service and surrender, and His incarnations, especially Rama and Krishna. Among the foremost means of communion is chanting His holy names. In most schools of Vaishnavism, God and soul are eternally distinct, with the soul’s destiny being to revel in God’s loving presence. ¶In Smartism, the Deity is Ishvara. Devotees choose their Deity from among six Gods, yet worship the other five as well: Vishnu, Siva, Shakti, Ganesha, Surya and Skanda. Ishvara appears as a human-like Deity according to devotees’ loving worship. Both God and man are, in reality, the Absolute, Brahman; though under the spell of maya, they appear as two. Jnana, enlightened wisdom, dispels the illusion. ¶In this Insight, along the lower section of the next four pages, you will find verses from the writings of seers of these four denominations that offer a glimpse of their perspectives on the nature of things ultimate.

Verses from Sages of Diverse Traditions

Smarta Hinduism

I bow to Govinda, whose nature is bliss supreme, who is the satguru, who can be known only from the import of all Vedanta, and who is beyond the reach of speech and mind. ¶Let people quote the scriptures and sacrifice to the Gods, let them perform rituals and worship the Deities, but there is no liberation without the realization of one’s identity with the atman; no, not even in the lifetime of a hundred Brahmas put together. ¶It is verily through the touch of ignorance that thou who art the Supreme Self findest thyself under the bondage of the non-Self, whence alone proceeds the round of births and deaths. The fire of knowledge, kindled by the discrimination between these two, burns up the effects of ignorance together with their root. ¶As a treasure hidden underground requires [for its extraction] competent instruction, excavation, the removal of stones and other such things lying above it and [finally] grasping, but never comes out by being [merely] called out by name, so the transparent Truth of the Self, which is hidden by maya and its effects, is to be attained through the instructions of a knower of Brahman, followed by reflection, meditation and so forth, but not through perverted arguments.

Adi Shankaracharya, Vivekachudamani, verses 1.1, 6, 47 & 65, translated by Swami Madhavananda

Vaishnava Hinduism

The intrinsic form of the individual soul consists of intuitive knowledge; it is dependent on God, capable of union with and separation from the body; it is subtle and infinitesimal; it is different and distinct in each body. ¶There are various types of individual souls, such as liberated, devoted and bound. The intrinsic form of the individual self is covered by the mirific power of Krishna. This covering can only be removed by Krishna’s grace. ¶Krishna is the Absolute, the Brahman, whose nature excludes all imperfection and is one mass of all noble qualities. He embodies the Theophanies and is identical with Vishnu himself. Radha, Krishna’s consort, is all radiant with joy, and is endowed with a loveliness that reflects His nature. She is always surrounded by thousands of attendant maids, symbolizing finite souls. She also grants every desire. Krishna is to be worshiped by all who seek salvation, so that the influx of the darkness of ignorance may cease. This is the teachings of the Four Youths to Narada, witness to all truth.

Sri Nimbarka, Dashashloki, 2, 4, 5, 8, translated by Geeta Khurana, Ph.D.

Shakta Hinduism

Siva, having freely taken limitations of body upon Himself, is the soul. As He frees Himself from these, He is Paramasiva (supreme consciousness). Self realization is the aim of human life. Through the realization of unity of guru, mantra, Goddess, the Self and powers of kundalini, inwardly manifested as faculties of consciousness and outwardly as women, the knowledge of the subjective Self is acquired. Bliss is the form of the absolute consciousness manifested in body. The five makaras reveal that Bliss. By the power of bhavana [intention, resolve] everything is achieved.

Parashurama-kalpasutra, Prathama-khanda, 5-6, 11-13

The real nature is realized by dwelling in the great spontaneity. A firm stay in the universal consciousness is brought about by the absorption of duality. The great union arises from the unification of male and female [principles], and the perceiver with the perceived. Upon the enjoyment of the triple bliss, the unfettered supreme consciousness involuntarily and suddenly [reveals itself]. With the immersion into the great wisdom comes freedom from merit and demerit.

Vatulanatha-sutra, 1, 4, 5, 8, 12

Translations by Arjuna Taranandanatha Kaulavadhuta

Saivite Hinduism

The Lord created the world, the dwelling place of man. How shall I sing His majesty? He is as mighty as Mount Meru, whence He holds sway over the three worlds; and He is the four paths of Saivam here below. ¶Those who tread the path of Shuddha Saivam stand aloft, their hearts intent on Eternal Para, transcending worlds of pure and impure maya, where pure intelligence consorts not with base ignorance and the lines that divide Real, unreal and real-unreal are sharply discerned.

Tirumantiram 1419 & 1420

This Lord of Maya-world that has its rise in the mind, He knows all our thoughts, but we do not think of Him. Some be who groan, “God is not favorable to me,” but surely God seeks those who seek, their souls to save. ¶“How is it they received God Siva’s grace?” you ask. In the battle of life, their bewildered thoughts wandered. They trained their course and, freed of darkness, sought the Lord and adored His precious, holy feet.

Tirumantiram 22 & 599

Translations by Dr. B. Natarajan

What Is Liberation?

aving lived many lives, each soul eventually seeks release from mortality, experiences the Divine directly through Self Realization and ultimately attains liberation from the round of births and deaths. All Hindus know this to be their eventual goal, but the means of attainment and understanding of the ultimate state vary greatly. The point in evolution at which the individual earns release and exactly what happens afterwards is described differently in each of the Hindu denominations. Within each sect there are also distinct schools of thought. These are the subtle, profound and compelling perspectives we explore below.

aving lived many lives, each soul eventually seeks release from mortality, experiences the Divine directly through Self Realization and ultimately attains liberation from the round of births and deaths. All Hindus know this to be their eventual goal, but the means of attainment and understanding of the ultimate state vary greatly. The point in evolution at which the individual earns release and exactly what happens afterwards is described differently in each of the Hindu denominations. Within each sect there are also distinct schools of thought. These are the subtle, profound and compelling perspectives we explore below.

Bliss: In a mountain cave, a worshiper of God as the Absolute Reality (Sivalinga) transcends the mind and completely realizes his oneness with all of creation. His samadhi is so deep that his outer identity dissolves, shown by the starry sky pervading his body

Having realized the Self, the rishis, perfected souls, satisfied with their knowledge, passion-free, tranquil—those wise beings, having attained the Ominipresent on all sides—enter into the All itself.

Atharva Veda, Mundaka Upanishad 3.2.5

he dawn of freedom from the cycle of reincarnation is called moksha (liberation), and one who has attained the state of liberation is called a jivanmukta (liberated soul). While some schools of Hinduism teach that liberation comes only upon death, most recognize the condition of jivanmukti, a state of liberation in which the spiritually advanced being continues to unfold its inherent perfection while in the embodied state. It is said of such a great one that “he died before he died,” indicating the totally real, not merely symbolic, demise of the ego, or limited self-sense. Some schools hold the view that liberated beings may voluntarily return to the physical universe in order to help those who are as yet unliberated.

he dawn of freedom from the cycle of reincarnation is called moksha (liberation), and one who has attained the state of liberation is called a jivanmukta (liberated soul). While some schools of Hinduism teach that liberation comes only upon death, most recognize the condition of jivanmukti, a state of liberation in which the spiritually advanced being continues to unfold its inherent perfection while in the embodied state. It is said of such a great one that “he died before he died,” indicating the totally real, not merely symbolic, demise of the ego, or limited self-sense. Some schools hold the view that liberated beings may voluntarily return to the physical universe in order to help those who are as yet unliberated.

The Sanskrit word moksha derives from the root muk, which has many connotations: to loosen, to free, release, let loose, let go and thus also to spare, to let live, to allow to depart, to dispatch, to dismiss and even to relax, to spend, bestow, give away and to open. Philosophically, moksha means “release from worldly existence or transmigration; final or eternal emancipation.” But moksha is not a state of extinction of the conscious being. Nor is it mere unconsciousness. Rather it is perfect freedom, an indescribable state of nondifferentiation, a proximity to, or a oneness with, the Divine. Moksha marks an end to the earthly sojourn, but it may also be understood as a beginning, not unlike graduation from university. Apavarga and kaivalya are other apt terms for this ineffable condition of perfect detachment, freedom and oneness.

Hinduism is a pluralistic tradition. On any given subject it offers a variety of views that reflect different human temperaments and different levels of emotional, intellectual, moral and spiritual development. So, too, on the subject of liberation, various learned opinions exist. Since liberation involves transcending time and space, and yet is a state that can be achieved while in a body, it defies precise definition. For this reason, some have argued that different views of liberation simply reflect the built-in limitations of language and reason.

Many Paths

The Vedas themselves present a number of approaches to liberation. Some of these are agnostic; others involve various monistic and theistic views. The main classical text on Self Realization within the Vedanta tradition, the Brahma Sutra of Badarayana, mentions a number of then current views: that upon liberation the soul (jiva) attains nondifference from Brahman (IV.4.4); that it gains the attributes of Brahman (IV.4.5); that it exists only as pure consciousness (IV.4.6); that even though it is pure consciousness from the relative standpoint, it can still gain the attributes of Brahman (IV.4.7); that through pure will alone it can gain whatever it wishes (IV.4.8); that it transcends any body or mind (IV.4.10); that it possesses a divine body and mind (IV.4.11); and that it attains all powers except creatorship, which belongs to Ishvara alone (IV.4.17). Generally, the view that the soul attains the Absolute only is more represented by the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, while the Chandogya Upanishad mentions liberation along with the attainment of lordly powers. Most later ideas of moksha are variations on these same Vedic views.

At one end of this metaphysical spectrum are the jnanis who follow the yoga of knowledge and who ascribe to the view that the Ultimate Reality is formless and unqualified (nirguna). At the other end are the bhaktas who follow the yoga of devotion and commonly believe that the individual being (jiva) remains in communion with its beloved (Bhagavan). Thus, devotees believe that they will come to inhabit the divine realm, or loka, of their chosen Deity, Siva, Vishnu, Kali, etc. Each metaphysical view has given rise to a distinct practical approach to reaching Oneness and Liberation.

Later Advaita Vedantins, such as Shankaracharya, spoke of two types of liberation. The first is complete or direct liberation, which they regarded as the highest state. The second is a gradual liberation that occurs wherein the individual being goes, after death, first to the heaven of Brahma and then gains liberation from there without having to return to the physical world.

Ramana Maharshi, the great sage of South India, observed that three types of liberation are mentioned in Hinduism: without form, with form, and both with and without form. He considered true liberation as transcending all such concepts (Saddarshana 42).

The Natha Saivite perspective is as follows. To attain liberation while living, the realization of the Self has to be brought through into every aspect of life, every atom of one’s body. This occurs after many experiences of nirvikalpa samadhi. Through harnessing the power of sannyasin and tapas, the adept advances his or her evolution. Only great tapasvins achieve jivanmukti, for one must be proficient in brahmacharya, yoga, pranayama and the varied sadhanas. It is a grace made possible by guidance of a living satguru and attained by single-minded and strong-willed discipline, worship, detachment and purification.

Thus, it is possible to realize the Self—as in nirvikalpa samadhi—and still not reach the emancipated state. If this happens, the being reincarnates in the physical world after death and in his new body has the opportunity to build upon past virtues and realizations until finally becoming a jivanmukta in that or a future birth.

What distinguishes the mukta from the nonliberated individual is his total freedom from all selfishness and attachments, his permanent abidance in the all-pervading Divine Presence, his lucid, witnessing consciousness and his wisdom (jnana), revealed in spontaneous utterances.

Even after attaining perfect liberation, a being may, after passing into the inner worlds, consciously choose to be reborn to help others on the path. Such a one is called an upadeshi—exemplified by the benevolent satguru—as distinguished from a nirvani, or silent ascetic who abides at the pinnacle of consciousness, whether in this world or the next, shunning all worldly involvement.

Summary

All schools are agreed that liberation is the ultimate fulfilment of human life, whose purpose is spiritual growth, not mere worldly enjoyment (bhoga). Having lived many lives and having learned many lessons, each conscious being seeks release from mortality, which then leads to glimpses of our divine origin and finally Self Realization. This consists in discovering our true nature, beyond body and mind, our identity in the incomprehensibly vast ultimate Being. Upon this discovery, we are released from the round of births and deaths and realize eternal freedom, untold bliss and supreme consciousness.

Views on the Nature of Soul and God

The concept of moksha for every Hindu school of thought is informed and modified by its understanding of the individual and its relationship to God. Most Hindus believe that after release from birth and death the innermost being will exist in the higher regions of the subtle worlds, where the Deities and spiritually mature beings abide. Some schools contend that the soul continues to evolve in these realms until it attains perfect union and merger with God. Others teach that the highest end is to abide eternally and separately in God’s glorious presence. Four distinct views, reflected in the primary Hindu denominations, are explored below.

Smarta Hinduism: All is Brahman

Smartism (the teaching following smriti, or tradition) is an ancient brahmanical tradition reformed by Adi Shankara in the ninth century. This liberal Hindu path, which revolves around the worship of six fundamental forms of the Divine, is monistic, nonsectarian, meditative and philosophical. Ishvara and the human being are in reality the singular absolute Brahman. Within maya, the soul and Ishvara appear as two. Jnana, spiritual wisdom, dispels that illusion.

Most Smartas believe that moksha is achieved through jnana yoga alone. This approach is defined as an intellectual and meditative but non-kundalini yoga path. Yet, many Advaitins also recognize the kundalini as the power of consciousness. Ramana Maharshi and Swami Shivananda of Rishikesh did, and Shankara wrote on tantra and kundalini as in the Saundarya-Lahiri. Guided by a realized guru and avowed to the unreality of the world, the initiate meditates on himself as Brahman to break through the illusion of maya. The ultimate goal of Smartas is to realize oneself as Brahman, the Absolute and only Reality. For this, one must conquer the state of avidya, ignorance, which causes the world to appear as real.

For the realized being, jivanmukta, all illusion has vanished, even as he lives out life in the physical body. If the sun were cold or the moon hot or fire burned downward, he would show no wonder. The jivanmukta teaches, blesses and sets an example for the welfare of the world. At death, his inner and outer bodies are extinguished. Brahman alone exists and he is That forever, all in All.

For Smartism, liberation depends on spiritual insight (jnana). It does not come from recitation of hymns, sacrificial worship or a hundred fasts. The human being is liberated not by effort, not by yogic practices, not by any self-transformation, but only by the knowledge gained from scripture and self-reflection that at its core the being is in fact Brahman. However, all such practices do help purify the body and mind and create the aptitude (adhikara) without which jnana remains mere theory or fantasy. Jnana yoga’s progressive stages are scriptural study (shravana), reflection (manana) and sustained meditation (nididhyasana or dhyana). Practitioners may also choose from three other nonsuccessive paths in order to cultivate devotion, accrue good karma, and purify the mind. These are bhakti yoga, karma yoga and raja yoga, which some believe can also bring enlightenment, as they lead to jnana.

Scripture teaches that “for the great-souled, the surest way to liberation is the conviction that ‘I am Brahman’ ” (Shukla Yajur Veda, Paingala Upanishad 4.19). Sri Jayendra Saraswati of Kanchi Peedam, Tamil Nadu, India, affirms, “That state where one transcends all feelings is liberation. Nothing affects this state of being. You may call it transcendental bliss, purified intuition that enables one to see the Supreme as one’s own Self. One attains to Brahman, utterly liberated.”

Vaishnava Hinduism: Forever at God’s Feet

The primary goal of Vaishnavites is videhamukti, disembodied liberation, attainable only after death when the “small self” realizes union with God Vishnu’s infinite body as a part of Him, yet maintains its pure individual personality. God’s transcendental Being is a celestial form residing in the city of Vaikuntha, the home of all eternal values and perfection, where the inner being joins Him when liberated. Beings, however, do not share in God’s all-pervasiveness or power to create.

Most Vaishnavites believe that dharma is the performance of various devotional disciplines (bhakti sannyasins), and that the human being can communicate with and receive the grace of Lord Vishnu, who manifests through the temple Deity, or icon. The paths of karma yoga and jnana yoga are thought to lead to bhakti yoga. Through total self-surrender, called prapatti, to Lord Vishnu, one attains liberation from the world of change (samsara). Vaishnavites consider the moksha of the Advaita philosophies a lesser attainment, extolling instead the bliss of eternal devotion. There are differing categories of souls that attain to four different levels of permanent release: salokya, or “sharing the world” of God; samipya, or “nearness” to God; sarupya, or “likeness” to God; and sayujya, or “union” with God. Jivanmukti exists only in the case of great souls who leave their place in the divine abode to take a human birth for the benefit of others and return to God as soon as their task is done.

There is one school of Vaishnavism, founded by Vallabhacharya, which takes an entirely different view of moksha. It teaches that upon liberation the soul, through its insight into truth revealed by virtue of perfect devotion, recovers divine qualities suppressed previously and becomes one with God, in identical essence, though the soul remains a part, and God the whole. This relationship is described by the analogy of sparks issuing from a fire.

Swami Prakashanand Saraswati of the International Society of Divine Love, Texas, offers a Vaishnava view, “Liberation from maya and the karmas is only possible after the divine vision of God. Thus, sincere longing for His vision is the only way to receive His grace and liberation.”

Shakta Hinduism: Refuge in the Mother

Shaktas believe that the soul is one with the Divine. Emphasis is given to the feminine aspect of the ultimate reality—Shakti. The Divine Mother or Goddess Power, Shakti, is the mediatrix bestowing this advaitic moksha on those who worship Her. Moksha is complete identification with the transcendental Divine, which is achieved when the kundalini shakti—the individuated form of the divine power—is raised through the sushumna current of the spine to the top of the head where it merges with Siva.

The spiritual practices in Shaktism, which is also known as tantra or tantrism, are similar to those in Saivism, though there is more emphasis in Shaktism on God’s power as opposed to mere Being or Consciousness. Shakta practices include visualization and rituals involving mantras, hand gestures (mudras), and geometric designs (yantras). The body is viewed as a temple of the Divine, and thus there are also numerous prescribed techniques for purifying and transforming the body. Philosophically, Shaktism’s yogic world view embraces all opposites: male-female, absolute-relative, pleasure-pain, cause-effect, mind-body. Shamanistic Shaktism employs magic, trance mediumship, firewalking and animal sacrifice for healing, fertility, prophecy and power. In “left-hand” tantric circles an antinomianism is evident, which seeks to transcend traditional moral codes.

The state of jivanmukti in Shaktism is called kulachara or “the divine way of life,” which is attained through sadhana and grace. The liberated soul is known as a kaula-siddha, to whom wood and gold, life and death are the same. The kaula-siddha can move about in the world at will, even returning to earthly duties such as kingship, yet remaining liberated from rebirth, as his actions can no longer bind him.

The Goddess, Devi, gives both mukti and bhukti—liberation and worldly enjoyment. Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan explained, “The jiva under the influence of maya looks upon itself as an independent agent and enjoyer until release is gained. Knowledge of Shakti is the road to salvation, which is dissolution in the bliss effulgence of the Supreme.” Shri Shri Shivaratnapuri Swami of Kailas Ashram, Bangalore, India, declares, “My message to mankind is right thought, right living and unremitting devotion to the Divine Mother. Faith is the most important thing that you should cultivate. By faith does one obtain knowledge.”

Saiva Hinduism: Soul and Siva Are One

The path for Saivites is divided into four progressive stages of belief and practice called charya, kriya, yoga and jnana. The soul evolves through karma and reincarnation from the instinctive-intellectual sphere into virtuous and moral living, then into temple worship and devotion, followed by internalized worship or yoga and its meditative disciplines. Union with God, Siva, comes through the grace of the satguru and culminates in the soul’s maturity into jnana, wisdom. Saivism values both bhakti and yoga, devotional and contemplative sadhanas.

Moksha is defined differently in Saivism’s six schools. 1) Pashupata Saivism emphasizes Siva as supreme cause and personal ruler of the soul and world. It teaches that the liberated soul retains its individuality in a state of complete union with Siva. 2) Vira Saivism holds that after liberation the soul experiences a true union and identity of Siva and soul, called Linga and anga. The soul ultimately merges in a state of Shunya, or Nothingness, which is not an empty void. 3) Kashmir Shaivism teaches that liberation comes through a sustained recognition, called pratyabhijna, of one’s true Self as nothing but Siva. After liberation, the soul has no merger in God, as God and soul are eternally nondifferent. 4) In Gorakhnath Saivism, or Siddha Siddhanta, moksha leads to a complete sameness of Siva and soul, described as “bubbles arising and returning to water.” 5) In Siva Advaita, liberation leads to the “akasha within the heart.” Upon death, the soul goes to Siva along the path of the Gods, continuing to exist on the spiritual plane, enjoying the bliss of knowing all as Siva, and attaining all powers except creation. This is a similar view to the Upanishads like the Chandogya and the Brahma Sutras.

The sixth, Saiva Siddhanta, has two subsects. Meykandar’s pluralistic realism teaches that God, soul and world are eternally coexistent. Liberation leads to a state of oneness with Siva in which the soul retains its individuality, as salt added to water.

Tirumular’s monistic theism, or Advaita Ishvaravada, the older of the two schools, holds that evolution continues after earthly births until jiva becomes Siva; the soul merges in perfect oneness with God, like a drop of water returning to the sea. Scriptures teach, “Having realized the Self, the rishis, perfected souls, satisfied with their knowledge, passion-free, tranquil—those wise beings, having attained the Omnipresent on all sides—enter into the All itself” (Mundaka Upanishad 3.2.5). The primary goal of this form of monistic Saiva Siddhanta is realizing one’s identity with God Siva, in perfect union and nondifferentiation. This is termed nirvikalpa samadhi, Self Realization, and may be attained in this life, granting moksha, permanent liberation from the cycles of birth and death. A secondary goal is savikalpa samadhi, the realization of Satchidananda, a unitive experience within superconsciousness in which perfect Truth, Consciousness and Bliss are known.

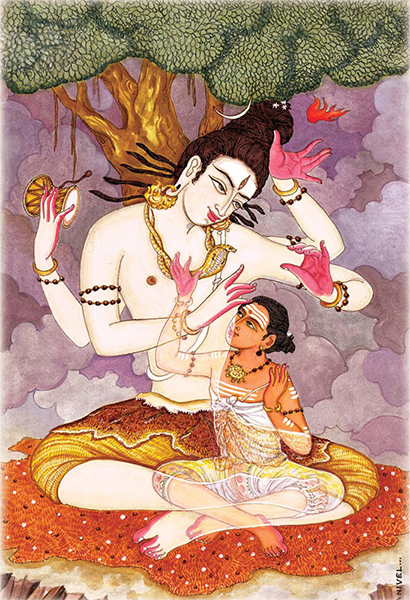

Union: Every soul’s ultimate goal, in this life or another, is to realize its oneness with God. That union is depicted here as Lord Siva and a mature soul merging in oneness. Siva sits beneath a banyan tree, bestowing His Grace by touching the third eye of the seeker, who reaches up to embrace Divinity.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

A Monistic Natha Saivite Conclusion

According to the Saiva Siddhanta philosophy of South India, to reach emancipation, beyond all pleasure and pain, all difference and decay, the being must successively remove the three fetters: karma, “the power of cause and effect, action and reaction;” maya, “the power of manifestation;” and anava, “the power of egoity or veil of duality.” Once freed by God’s grace from these bonds (which do not cease to exist altogether, but no longer have the power to bind), the being is in the permanent state of sahaja samadhi, or “natural, spontaneous ecstasy,” the living illumination called jivanmukti. This is the realization of the timeless, spaceless and formless Reality beyond all change or diversity. Simultaneously it is the realization that all forms, whether internal or external, are also aspects of this Ultimate Reality.

Moksha does not mean death, as some misunderstand it. It means freedom from rebirth, before or at the point of death, after which souls continue evolving in the inner worlds, the Antarloka and Sivaloka, and finally merge with Lord Siva as does river water when returning to the ocean. Moksha comes when all earthly karmas have been fully resolved. Finally, at the end of each soul’s evolution comes vishvagrasa, total absorption in Siva. The Vedas promise, “If here one is able to realize Him before the death of the body, he will be liberated from the bondage of the world.”

All embodied souls—whatever be their faith or convictions, Hindu or not—are destined to achieve moksha, but not necessarily in this life. Hindus know this and do not delude themselves that this life is the last. Old souls renounce worldly ambitions and take up sannyasa, renunciation, in quest of Self Realization even at a young age. Younger souls desire to seek lessons from the experiences of worldly life, which is rewarded by many, many births on Earth. In between, souls seek to fulfil their dharma while resolving karma and accruing merit through good deeds. After moksha has been attained—and it is an attainment resulting from much sadhana, self-reflection and realization—subtle karmas are made and swiftly resolved, like writing on water. “The Self cannot be attained by the weak, nor by the careless, nor through aimless disciplines. But if one who knows strives by right means, his soul enters the abode of God” (Mundaka Upanishad 3.2.4).

his chart assembles and correlates four essential elements of Hindu cosmology: the planes of existence and consciousness; the tattvas; the chakras; and the bodies of man. ¶It is organized with the highest consciousness, or subtlest level of manifestation, at the top, and the lowest, or grossest, at the bottom. In studying the chart, it is important to remember that each level includes within itself all the levels above it. Thus, the element earth, the grossest or outermost aspect of manifestation, contains all the tattvas above it on the chart. They are its inner structure. Similarly, the soul encased in a physical body also has all the sheaths named above—pranic, instinctive-intellectual, cognitive and causal.

his chart assembles and correlates four essential elements of Hindu cosmology: the planes of existence and consciousness; the tattvas; the chakras; and the bodies of man. ¶It is organized with the highest consciousness, or subtlest level of manifestation, at the top, and the lowest, or grossest, at the bottom. In studying the chart, it is important to remember that each level includes within itself all the levels above it. Thus, the element earth, the grossest or outermost aspect of manifestation, contains all the tattvas above it on the chart. They are its inner structure. Similarly, the soul encased in a physical body also has all the sheaths named above—pranic, instinctive-intellectual, cognitive and causal.

The three columns on the left side of the chart depict the inner and outer universe. Column one shows the three worlds: the causal, superconscious realm of the Gods; the astral realm of dreams, abode of non-embodied souls; and the physical world of the five senses.

Column two gives a more detailed division in 14 planes and correlates these to the chakras, the force centers of consciousness resident within each soul. It shows three levels in the third world, corresponding to the sahasrara, ajna and vishuddha chakras; and three levels of the second world, or astral plane, corresponding to the anahata, manipura and svadhishthana chakras. Note that the grossest of these planes, the Bhuvarloka or Pitriloka, has a secondary realm, called the Pretakoka, where abide earth-bound astral entities. The first world, or Bhuloka, corresponds to the muladhara chakra. Below it is depicted the part of the astral plane called the Narakaloka—the realm of lower consciousness, fear, anger, jealousy, etc. Looking back to column one, the dotted path indicates that regions two, three and four of the Antarloka are the domain from which souls are reborn. Column three provides a view of the kalas, which emphasize the states of mind or levels of consciousness associated with these strata.

Column four of the chart lists the 36 tattvas. Tattvas (literally “that-ness”) are the primary principles, elements, states or categories of existence, the building blocks of the universe. God constantly creates, sustains the form of and absorbs back into Himself His creations. Rishis describe this emanational process as the unfoldment of tattvas, stages or evolutes of manifestation, descending from subtle to gross. This column of the chart subdivides the tattvas into three levels of maya, manifest creation, as follows: shuddha maya (correlating to the Third World in column one); shuddhashuddha maya (corresponding to the Maharloka); and ashuddha maya (corresponding to the mid-astral, lower astral and physical planes). Column five lists the three bodies of the soul: causal, subtle and physical (which correspond directly to the three worlds); and the five sheaths (anandamaya, vijnanamaya, manomaya, pranamaya and annamaya). Note the correlation of these and the worlds by reading across the chart to the left to the two columns named “3 worlds” and “14 planes.” For more details on the subjects and terms in the chart, you can search for definitions at: www.himalayanacademy.com/resources/lexicon/