Symbol of Auspiciousness§

Swastikam§

स्वस्तिकम्§

OING BACK FIVE THOUSAND YEARS IN HISTORY, AT THE PORT OF LOthal on India’s northern coast of the Arabian Sea, tons of cargo lines the wharves. A trader, inspecting his goods before voyaging to Sumerian cities on the Tigris River, turns an imprinting seal over in his hands, feeling its upraised image of a cross with arms sweeping ninety degrees leftward from each endpoint of the cross. Swiftly he presses the seal into a soft clay tag anchored to a bundle of cotton. The impression is a mirror image of the seal, a right-hand facing swastika. The symbol, so evocative of unending auspiciousness, is also sewn into his sails, just as the swastika also adorns the sails of a ship described in the Rāmāyaṇa. The trader is from Hinduism’s most ancient known civilization: the Indus Valley in northwest India. The seal rests today in a museum and is the oldest surviving representation of the swastika, a Sanskrit word meaning “good being, fortune or augury,” literally “conducive to well-being,” derived from su, “well” and astu, “may it be,” or “be it so.”§

OING BACK FIVE THOUSAND YEARS IN HISTORY, AT THE PORT OF LOthal on India’s northern coast of the Arabian Sea, tons of cargo lines the wharves. A trader, inspecting his goods before voyaging to Sumerian cities on the Tigris River, turns an imprinting seal over in his hands, feeling its upraised image of a cross with arms sweeping ninety degrees leftward from each endpoint of the cross. Swiftly he presses the seal into a soft clay tag anchored to a bundle of cotton. The impression is a mirror image of the seal, a right-hand facing swastika. The symbol, so evocative of unending auspiciousness, is also sewn into his sails, just as the swastika also adorns the sails of a ship described in the Rāmāyaṇa. The trader is from Hinduism’s most ancient known civilization: the Indus Valley in northwest India. The seal rests today in a museum and is the oldest surviving representation of the swastika, a Sanskrit word meaning “good being, fortune or augury,” literally “conducive to well-being,” derived from su, “well” and astu, “may it be,” or “be it so.”§

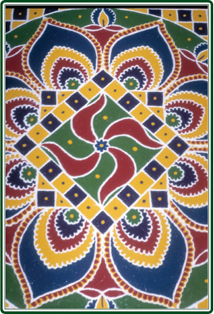

For Hindus the swastika is a lucky cross associated with the good fortunes given by Lord Gaṇeśa. It also represents the sun and the cycle of life. This ancient benign symbol is used today by housewives to guard thresholds and doors, by priests to sanctify ceremonies and offerings, and by businessmen to bless the opening pages of account books each New Year’s day. No ceremony or sacrifice is considered complete without it, for it is believed to have the power to ward off misfortune and negative forces. A series of small swastikas is a favorite border pattern for textiles. In Mahārāshṭra, the rainy season is especially devoted to its honor, when it is drawn on the floor in elaborate patterns using colorful powders and flower petals.§

It is said that the swastika’s right-angled arms reflect the fact that the path toward our objectives is often not straight, but takes unexpected turns. They denote also the indirect way in which Divinity is reached—through intuition and not by intellect. Symbolically, the swastika’s cross is said to represent God and creation. The four bent arms stand for the four human aims, purushārtha: righteousness, dharma; wealth, artha; love, kāma; and liberation, moksha. Thus it is a potent emblem of Sanātana Dharma, the eternal truth. It also represents the world wheel, eternally turning around a fixed center, God. The swastika is associated with the mūlādhāra chakra, the center of consciousness at the base of the spine, and in some yoga schools with the maṇipūra chakra at the navel, the center of the microcosmic sun (sūrya).§

Throughout Earth’s Cultures§

The swastika is a sacred sign of prosperity and auspiciousness, perhaps the single most common emblem in Earth cultures. As the Encyclopaedia Britannica explains, “It was a favorite symbol on ancient Mesopotamian coinage; it appeared in early Christian and Byzantine art (where it became known as the gammadion cross because its arms resemble the Greek letter gamma, Γ); and it occurred in South and Central America (among the Mayans) and in North America (principally among the Navajos). In India it continues to be the most widely used auspicious symbol of Hindus, Jainas and Buddhists.”§

The swastika is a sacred sign of prosperity and auspiciousness, perhaps the single most common emblem in Earth cultures. As the Encyclopaedia Britannica explains, “It was a favorite symbol on ancient Mesopotamian coinage; it appeared in early Christian and Byzantine art (where it became known as the gammadion cross because its arms resemble the Greek letter gamma, Γ); and it occurred in South and Central America (among the Mayans) and in North America (principally among the Navajos). In India it continues to be the most widely used auspicious symbol of Hindus, Jainas and Buddhists.”§

When Buddhism emerged from India’s spiritual wellspring, it inherited the right-angled emblem. Carried by monks, the good-luck design journeyed north over the Himalayas into China, often carved in statues into Buddha’s feet and splayed into a spectrum of decorative meandering or interconnecting swastikas. On the other side of the planet, American Indians inscribed the spoked sign of good luck into salmon-colored seashells, healing sticks, pottery, woven garments and blankets. Two thousand miles south, the Mayans of the Yucatan chiseled it into temple diagrams. Once moored to the ancient highland cultures of Asia Minor, the emblem later voyaged around the Mediterranean, through Egypt and Greece, northward into Saxon lands and Scandinavia and west to Scotland and Ireland.§

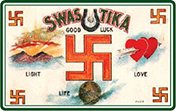

Nineteenth-century Americans picked up the symbol from the American Indians. Boy Scouts wore brassy swastika belt buckles, and a US World’s Fair early last century minted flashy swastika commemorative coins. It was displayed in jewelry and inscribed on souvenirs, light fixtures, postcards and playing cards. In the 1920s and early 30s the swastika was the emblem of the United States’ 45th Infantry Division, proudly worn by soldiers on their left shoulder as an ancient good-luck symbol, in yellow on a square red background. The emblem was changed to an Native American thunderbird in the 1930s. Canada has a town called Swastika, 360 miles north of Toronto, named in 1911 after a rich gold mine. When WWII broke out, the townsfolk withstood pressures from the federal government to change the name to Winston.§

Misappropriated by the German Nazis§

In the 1930s, when Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Third Reich rose to power in Germany and engulfed the planet in World War II, the fortunes of the swastika declined. From September 1935 to the fall of the Nazis in 1945, it was displayed on the Reich’s official flag, a black swastika in a white circle against a red field. German soldiers also wore the hackenkrenz (“hooked cross”) on their uniforms, in a circle beneath an eagle, and displayed it on their armory. In the West it became an infamous, hated symbol of fascism and anti-Semitism and was banned by the Allied Command at the war’s end, though the swastika’s history is as extensive in the West as in Asia.§

Tracking the Swastika’s Left and Right Forms§

The swastika has throughout history mutated into a wide diversity of forms and meanings, but in its Hindu usage the right-hand swastika is far more prevalent and ancient than its left-hand counterpart.§

The swastika has throughout history mutated into a wide diversity of forms and meanings, but in its Hindu usage the right-hand swastika is far more prevalent and ancient than its left-hand counterpart.§

Next to the Indus seal, the oldest Indian swastika motif appears abundantly on the early Buddhist sculptures, a period when Buddha was not depicted in human form—only by his footprints surrounded by dozens of right-hand swastikas. Similarly, the Jain emblem for their seventh Tīrthaṅkara (pathfinder) is the symbol of the sun, the right-turning swastika. In Malaysia, Sikh shrines all have right-hand swastikas as mystical ornamentation. In some sources, neither swastika was assigned a negative connotation: the right-hand was a spring solar, male symbol and the left was an autumn solar, female mark. As the tantric sciences of Śaivism and Śāktism bifurcated into left-hand and right-hand paths (the vāma and dakshiṇa), the swastika may have followed into black or white mysticism and magic.§

The search for a pre-World War II treatise on the swastika struck gold with a book entitled The Swastika: the Earliest Known Symbol and its Migrations, by Thomas Wilson, a curator of the US National Museum. Written in 1894 for the Smithsonian Institute, the work opens with a right-hand swastika on the title page and presents an exhaustive survey of the global dispersion of this symbol, from the Navajo tribes of North America to Egypt, ancient Troy and the Taoists of China.§

Among other Oriental scholars quoted in the book is Max Müller, the German professor at Oxford and Veda translator who introduced the word Aryan to the European intelligentsia. It was through Müller that Aryan was first imbued with a sense of race rather than an attribute of virtuous, spiritual nobility. Wilson writes, “Prof. Max Müller makes the symbol different according as the arms are bent to the right or left. That bent to the right he denominates the true swastika, that bent to the left he calls suavastika, but he gives no authority for the statement.” After examining the positions of dozens of scholars, Wilson concludes, “Therefore, the normal swastika would seem to be that with the ends bent to the right.”§

Wilson’s book pictorially surveys the dispersion of the swastika symbol, region by region. Indeed, so broadly cast is the symbol in the early ages of human society that Wilson determines it is impossible to trace the swastika’s origin. Wilson’s exploration of European use of the swastika prior to 1894 is an eye-opener. In the section “Germany and Austria” we are treated to ten samples of the swastika (now displayed in museums) that are designed into filigree screens, used to ornament burial urns and spearheads, and fashioned into broach and pin jewelry. They orient both right and left, with a preference to the right. The entirety of runic Europe was covered with swastikas, both in ornamentation and in some of their best-preserved Teutonic inscriptions to the old Gods.§

The Right-Hand Swastika§

The swastika is an emblem of geometric perfection. In the mind’s eye it can be stable and still or whirl in perpetual motion, its arms rotating one after another like a cosmic pinwheel. It is unknown why and how the term swastika, “may it be good,” was wedded to this most ancient and pervasive of symbols. Most authorities designate the right-hand swastika as a solar emblem, capturing the sun’s path from east to west, a clockwise motion. One theory says it represents the outward dispersion of the universe. One of its finest meanings is that transcendent reality is not attained directly through the logic of the mind, but indirectly and mysteriously through the intuitive, cosmic mind. Though Hindus usually use the swastika straight up and down, other cultures rotated it at various angles.§

The Left-Handed Swastika§

The left-hand swastika appears in many cultures, including Hindu. It often is used interchangeably with the right-hand version, though the majority of Hindus employ the right-facing form. One school sees this swastika as that which rotates clockwise because a wind blowing across its face would catch the arms and rotate it to the right. But this is an unusual interpretation. Most see it as rotating anti-clockwise, as the arms point as such. Some say this form signifies the universe imploding back into its essence. It has been associated with the vāma, left-handed, mystic path that employs sensual indulgence and powerful Śākta rites, with night, with the Goddess Kālī and with magical practices. Another interpretation is that it represents the autumn solar route, a time of dormancy.§

The left-hand swastika appears in many cultures, including Hindu. It often is used interchangeably with the right-hand version, though the majority of Hindus employ the right-facing form. One school sees this swastika as that which rotates clockwise because a wind blowing across its face would catch the arms and rotate it to the right. But this is an unusual interpretation. Most see it as rotating anti-clockwise, as the arms point as such. Some say this form signifies the universe imploding back into its essence. It has been associated with the vāma, left-handed, mystic path that employs sensual indulgence and powerful Śākta rites, with night, with the Goddess Kālī and with magical practices. Another interpretation is that it represents the autumn solar route, a time of dormancy.§

The Swastika after Hitler§

Because of its infamous association with the Third Reich, the swastika was and still is abhorred by many inside and outside of Germany, still held in disparagement and misunderstanding, which itself is understandable though unfortunate. Now is a time for this to change, for a return to this solar symbol’s pure and happy beginnings. Ironically, even now Hindus managing temples in Germany innocently display on walls and entryways the swastika, the ancient symbol of Lord Gaṇeśa and more recently the hated insigne of Nazism, alongside the shaṭkona, six-pointed star, the ancient symbol representing God Śiva and Lord Kārttikeya and as Star of David, the not so ancient but cherished already for centuries emblem of Judaism.§

Swastika and the Chakras§

From a mystically occult point of view the swastika is a type of yantra, a psychic diagram representing the four-petalled mūlādhāra chakra located at the base of the spine within everyone. The chakras are nerve plexuses or centers of force and consciousness located within the inner bodies of man. In the physical body there are corresponding nerve plexuses, ganglia and glands. The seven principal chakras can be seen psychically as colorful, multi-petalled wheels or lotuses situated along the spinal cord. The seven lower chakras, barely visible, exist below the spine.§

CHAKRAS ABOVE THE BASE OF THE SPINE§ |

||

14) sahasrāra§ |

crown of head§ |

illumination§ |

13) ājñā§ |

third eye§ |

divine sight§ |

12) viśuddha§ |

throat§ |

divine love§ |

11) anāhata§ |

heart center§ |

direct cognition§ |

10) maṇipūra§ |

solar plexus§ |

willpower§ |

9) svādhishṭhāna§ |

below navel§ |

reason§ |

8) mūlādhāra§ |

base of spine§ |

memory/time/space§ |

CHAKRAS BELOW THE BASE OF THE SPINE§ |

||

7) atala§ |

hips§ |

fear and lust§ |

6) vitala§ |

thighs§ |

raging anger§ |

5) sutala§ |

knees§ |

retaliatory jealousy§ |

4) talātala§ |

calves§ |

prolonged confusion§ |

3) rasātala§ |

ankles§ |

selfishness§ |

2) mahātala§ |

feet§ |

absence of conscience§ |

1) pātāla§ |

soles of feet§ |

malice and murder§ |

Śivāchārya priests, adept in temple mysticism, testify that when they tap the sides of their head with their fists several times at the outset of pūjā, they are actually causing the amṛita, the divine nectar, to flow from the sahasrāra chakra at the top of their head, thus giving abhisheka, ritual anointment, to Lord Gaṇeśa seated upon the mūlādhāra chakra at the base of the spine.§

The Soul’s Evolution through the Chakras§

Devotees sometimes ask, “Why is it that some souls are apparently more advanced than others, less prone to the lower emotions that are attributes of the lower chakras?” The answer is that souls are not created all at once. Lord Śiva is continually creating souls. Souls created a long time ago are old souls. Souls created not so long ago are young souls. We recognize an old soul as being refined, selfless, compassionate, virtuous, controlled in body, mind and emotions, radiating goodness in thought, word and deed. We recognize a young soul by his strong instinctive nature, selfishness, lack of understanding and absence of physical, mental and emotional refinement.§

Devotees sometimes ask, “Why is it that some souls are apparently more advanced than others, less prone to the lower emotions that are attributes of the lower chakras?” The answer is that souls are not created all at once. Lord Śiva is continually creating souls. Souls created a long time ago are old souls. Souls created not so long ago are young souls. We recognize an old soul as being refined, selfless, compassionate, virtuous, controlled in body, mind and emotions, radiating goodness in thought, word and deed. We recognize a young soul by his strong instinctive nature, selfishness, lack of understanding and absence of physical, mental and emotional refinement.§

At any given time there are souls of every level of evolution. My satguru, Sage Yogaswami, taught that “The world is a training school. Some are in kindergarten. Some are in the B.A. class.” Each soul is created in the Third World and evolves by taking on denser and denser bodies until it has a physical body and lives in the First World, the physical plane. Then as it matures, it drops off these denser bodies and returns to the Second and Third Worlds, the astral and causal planes.§

This process of maturation, occurring over many, many lifetimes, is the unfoldment of consciousness through the chakras. First the young soul slowly matures through the pātāla, mahātala, rasātala and the talātala chakras. Such individuals plague established society with their erratic, adharmic ways. Between births, on the astral plane, they are naturally among the asuras, making mischief and taking joy in the torment of others. When lifted up into jealousy, in the sutāla chakra, there is some focus of consciousness, and the desires of malice subside. Finally, the pātāla chakra sleeps. Later, when the sutāla forces of jealousy are thwarted, the young soul arises into anger, experiencing fits of rage at the slightest provocation. As a result of being disciplined by society through its laws and customs, the individual slowly gains control of his forces; and a conscience begins to develop. It is at this stage that a fear of God and the Gods begins to manifest. Now, totally lifted up into the atala chakra, seventh of the fourteen force centers, the individual emerges into the consciousness of the mūlādhāra, the seat of the elephant God; and several of the chakras below cease to function. Here begins the long process of unfoldment through the higher chakras, a process outlined in Śaiva Siddhanta as the progressive path of charyā, kriyā, yoga and jñāna.§

Thus, through hundreds of lifetimes and hundreds of periods between births, the asura becomes the deva, and the deva becomes the Mahādeva until complete and ultimate merger with Śiva, viśvagrāsa. Individuality is lost as the soul becomes Śiva, the creator, preserver, destroyer, veiler and revealer. Individual identity expands into universality.§

Our loving Gaṇeśa, sitting on the mūlādhāra chakra, signified by the swastika, is “there for us’’ throughout our evolution from one set of four chakras to the next until all seven of the highest are functioning properly. He and His brother, Lord Murugan, work closely together to bring us all to Lord Śiva’s feet, into His heart, until jīva becomes Śiva.§